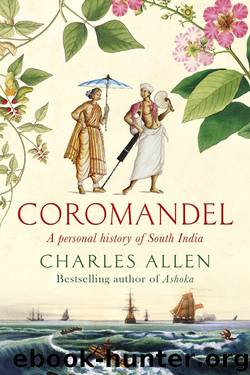

Coromandel by Charles Allen

Author:Charles Allen [ALLEN, CHARLES]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781408705407

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Published: 2017-11-02T04:00:00+00:00

The archaeologist and Sanskritist Rajendralala Mitra, author of Antiquities of Orissa.

Part of the Lingaraja temple complex in Bhubaneshwar.

One of the many puzzles of the Ashokan era is why that great emperor, having introduced a pan-Indian script, should have stuck with India’s remarkably crude system of punch-marked coinage when his Greek neighbours next door were producing high-quality coins bearing the ruler’s portrait and name on the obverse and images of their deities on the reverse. Such coins only began to appear in India in the first half of the second century CE during the rule of the Kushan king Kanishka, whose kingdom of Gandhara extended deep into Northern India and who came to be regarded by Chinese Buddhists as a second Ashoka even though his coinage shows him to have patronised a range of Vedic, Zoroastrian and Graeco-Bactrian deities besides Buddhism.

One of these gods was Oesho, a deity largely derived from the proto-Vedic wind god Vayu, who came into his own during the extended rule of King Kanishka’s father Vima Kadphises (c. 95–127 CE). Coins from this time show Oesho in several different forms: in aniconic form as a trident to which is attached the blade of a battle-axe, an erect phallus and a vajra (thunderbolt); as a naked ithyphallic human figure, holding a trident-cum-battle-axe in one hand and a stylised animal skin in the other; and as a crowned figure clad in a dhoti and accompanied by his vehicle, the bull Nandi – at which point he can definitely be said to be more Shiva than Oesho (see page 211). By the time Kanishka comes to the throne in about 127 CE Shiva has started to be depicted with three faces and four arms, even though still named as Oesho – and still arguably ithyphallic.

Just as Lord Shiva set the pace among the Hindu gods north of the Narmada, so a very similar process took place in the Deccan and worked its way southwards with Lord Shiva made manifest as Shiva linga, the unmistakable human phallus. Nowhere is this more magnificently and puzzlingly displayed than in a tiny Parasurameswara temple at Gudimallam, an otherwise insignificant hamlet lying about 30 kilometres to the south-east of Tirupati in southern Andhra Pradesh. This is now a scheduled monument maintained by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) – and with good cause, because at its heart is the truly remarkable Gudimallam Shivalinga, rising out of the floor to a height of about 5 feet (1.5 metres), an unmistakably rampant phallus carved in hard dark stone with the figure of Lord Shiva in warrior pose on the front (see below).

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4387)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4209)

World without end by Ken Follett(3476)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3463)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3201)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(3169)

The Queen of Nothing by Holly Black(2588)

City of Djinns: a year in Delhi by William Dalrymple(2555)

Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Treasures of Central Asia by Peter Hopkirk(2463)

India's Ancient Past by R.S. Sharma(2451)

Inglorious Empire by Shashi Tharoor(2437)

Tokyo by Rob Goss(2428)

In Order to Live: A North Korean Girl's Journey to Freedom by Yeonmi Park(2391)

Tokyo Geek's Guide: Manga, Anime, Gaming, Cosplay, Toys, Idols & More - The Ultimate Guide to Japan's Otaku Culture by Simone Gianni(2372)

India's biggest cover-up by Dhar Anuj(2352)

The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia by Peter Hopkirk(2345)

Goodbye Madame Butterfly(2251)

Batik by Rudolf Smend(2179)

Living Silence in Burma by Christina Fink(2069)